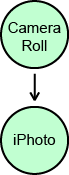

I took some pictures on my iPad. Then I used iTunes to sync with the Mac. I even specified iPad back up. But when I went looking for them on my Mac, the iPad Camera Roll pics were no where to be found. I was sure I did something wrong because that’s how I got photos from Mac to iPad. It turned out that getting pics from the iPad required me to use iPhoto for the transfer to the Mac.

I took some pictures on my iPad. Then I used iTunes to sync with the Mac. I even specified iPad back up. But when I went looking for them on my Mac, the iPad Camera Roll pics were no where to be found. I was sure I did something wrong because that’s how I got photos from Mac to iPad. It turned out that getting pics from the iPad required me to use iPhoto for the transfer to the Mac.

This illustrates the key difference between a traditional computer, and the way files are organized in iOS. On a Mac or PC there is common storage that all software can access. In iOS files are organized around apps. Each application and its files are grouped together like high school cliques. When an app gets built from the ground up, one way to guarantee that files can move to/from iOS devices is also create software for the computer it syncs with. Now back to my photos.

Suddenly iPhoto is valuable to me for two reasons: I can work on pics, and I can move pics off of the iPad. That’s not a huge deal, except Photoshop and Gimp do not move any iOS files. Apple “baked in” this iOS capability. Pictures and the iOS apps that use them benefit by having hooks in related software on desktop/laptop machines. It encourages a kind of microcosm based around a file type, in this case photos.

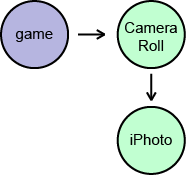

The iPad Camera isn’t the only app that creates or uses pics. For example, there are often prompts to take a screen shot of completed puzzles, rewards, etc. in game apps. Those pics are sent to the Camera Roll. Camera Roll to iPhoto becomes a file transfer path for these other apps. So instead of building a direct path between the device and computer on an app by app basis, developers can instead piggyback an existing, common path in a file type ecosystem. For example, audio files could leave via iTunes.

The iPad Camera isn’t the only app that creates or uses pics. For example, there are often prompts to take a screen shot of completed puzzles, rewards, etc. in game apps. Those pics are sent to the Camera Roll. Camera Roll to iPhoto becomes a file transfer path for these other apps. So instead of building a direct path between the device and computer on an app by app basis, developers can instead piggyback an existing, common path in a file type ecosystem. For example, audio files could leave via iTunes.

One of the most common transfer paths found in any app are email and social media. But these won’t help folks who work with large files because email and social media apps limit file size.

There is yet another way to wrangle data in iOS, bringing our total number of schemes to three:

(1) Direct file management with purpose built software for device and computer

(2) Pass files to another app that already has a transfer path

(3) Third party file management software such FileApp and DiskAid

It is worth noting that a device wide solution – one that approximates file management on a Mac/PC – requires that you connect to a traditional computer and run software on BOTH ends of the sync cable. I should also admit that I haven’t used this approach personally, so I don’t know how well it compares to the drag-and-drop file transfer with which most of us are already familiar.

Apple’s iCloud service is notable because it allows file storage in a second location without having a traditional computer present. But any remote storage – iCloud or a competitor – requires wireless data transfer, which can be pricey and can restrict where you are able to access it, especially for WiFi only devices. To work on an iOS device instead of a computer, wireless is your only option for backing up. Don’t be confused though: iCloud isn’t designed for you to move any file you want. No, it is designed for full device backup along with some data synchronization between devices and computers [Macworld iCloud article]. Regardless whether you use wireless remote storage or sync with a host computer, the decentralized iOS file structure forces you to take one of the three paths to/from devices.

Apple’s iCloud service is notable because it allows file storage in a second location without having a traditional computer present. But any remote storage – iCloud or a competitor – requires wireless data transfer, which can be pricey and can restrict where you are able to access it, especially for WiFi only devices. To work on an iOS device instead of a computer, wireless is your only option for backing up. Don’t be confused though: iCloud isn’t designed for you to move any file you want. No, it is designed for full device backup along with some data synchronization between devices and computers [Macworld iCloud article]. Regardless whether you use wireless remote storage or sync with a host computer, the decentralized iOS file structure forces you to take one of the three paths to/from devices.

It seems iOS inherits an awful lot from the iPod – a device designed for music playback, not music creation. The iPhone and iPad follow that perspective of consumption rather than production. If one primarily watches / listens / reads, the file management system makes it relatively simple to get data on the device. But to compose, shoot, record, edit, process, etc., iOS forces professionals to figure out how to move data off of the device. Which is the best path for backup in a given scenario? How should files be passed along to other collaborators? Which path works well for distributing finished work to clients and consumers? The answers will vary depending on the paths that have been built or co-opted by the app developer, access to a computer, and access to a wireless network.

See Also: The Right Tools for the Job, a series that compares Desktop, Laptop, Tablet, and Handheld.

Consider these storage options for media production.

Remote Storage

Remote servers and cloud storage help protect against fire, theft and other local disasters. Personally I consider those events less threatening than drive failure or accidental deletion. The cost in price per GB and transfer time for remote storage doesn’t seem as desirable to me as a spare, external hard drive. But it’s worth noting that Gobbler can be configured to backup while recording is in progress, saving time.

UPDATE Jul 18, 7:40pm PDT

Beware these known security flaws with remote file storage: FTP and Dropbox.

External Drives

External Drives

I find external drives the most practical and cost effective overall. I use them for active storage, backups and archives. I insist on internal power supplies with IEC power cables (as pictured above). Separate power supplies can too easily be separated from the enclosure, in which case the drive becomes an expensive brick.

Dispair not if you’ve already purchased drives with separate power supplies. You can strap it to the enclosure (see pic, right). It’s not ideal and you need to make sure it doesn’t overheat when used for hours. But for backups and long term archives this trick helps ensure you can get your files when you need them.

Dispair not if you’ve already purchased drives with separate power supplies. You can strap it to the enclosure (see pic, right). It’s not ideal and you need to make sure it doesn’t overheat when used for hours. But for backups and long term archives this trick helps ensure you can get your files when you need them.

UPDATE: July 18, 10:00pm PDT

A few sources for external drives with internal power supplies and IEC connectors:

Glyph, Maxx Digital, Avastor

Tape and Optical

People seem to like these for backups and long term archives. They can be cost effective in price per GB, but I have better things to do with my time than wait for data transfer to/from tape or optical disk. For me the time cost is far too high.

RAID

A redundant array of drives can be inexpensive per GB but your initial capital investment may be high. The most significant advantage: everything you do is copied while you work. It’s like recording to a separate device simultaneously without any extra effort. That makes RAID for active storage a safety and a backup all rolled into one. It’s not only cost effective in terms of storage space but also time saved.

Removable

Removable

Voyager style storage — where drive mechanisms are used like data cartridges — is an interesting twist on removable media. It behaves just like a regular hard drive because it is. You cut the cost of the enclosure, power supply, etc. off of every drive and only pay for it in the dock. When the drive is too full to keep using (before it reaches 90%) you simply buy another mechanism. When not in use, store the drives in electrostatic bags and packing foam.

These flavors are not mutually exclusive. Combine a few for maximum advantage.

Active Storage – Where you keep your files while production is in progress.

Safety – A parallel recording system that acquires data simultaneously to the primary system.

Backup – A copy of your files at regular intervals. I prefer once a day.

Archive – Long term storage for completed projects after months of inactivity.

Read more about Media Storage and Business Continuity & Disaster Recovery.

If I learned anything from Cogan and Clark’s book Temples of Sound it is this: studios don’t sound amazing the first day. It takes time and thought — gradually tweaking things, fixing the weak areas — to bring a studio from merely usable to excellent.

I’ve been struggling with monitoring at my home studio. My initial setup was not inspiring confidence, but I couldn’t put my finger on root causes. My first instinct — the speakers were too close to the rear wall, so I pulled the desk an additional two feet away. That sounded a little better, but still wonky. Next I installed some frictional absorption panels, which tidied up the room overall but did not clean up the strangeness I was hearing. I started to suspect my handmade speaker stands made of wood with neoprene pads to help isolate from the desk. I wondered if the isolation was poor. I used some left over packing foam to replace my wooden stands. The upper bass felt so much better, but the lowest lows were weak. It was an improvement but I didn’t like the trade-off. Then I remembered a concept for improving bass accuracy in speakers.

A few years ago I heard a demonstration of the Primacoustic Recoil Stabilizer at a trade show. It made a significant difference in accuracy for the NS-10s they were using in the demo. The idea was so elegant it wasn’t difficult imagining how I might make my own version. Back in my studio, staring at the foam under my speakers, I decided it was time to try.

I went to the hardware store and bought four concrete bricks at a whopping price of $0.47 each. I put two bricks on top of the foam then speaker on the bricks. The concept: if the speaker has more mass the cabinet will move less, allowing a more efficient push/pull of the cone. It’s like giving a sprinter a starting block for a better push off. Sure enough I got my bass back. Not only was the bass full, it sounded tighter and more accurate than any configuration I’ve tried so far. Now one of the consequences is that the foam is carrying a heavier load, which somewhat compromises the isolation; I can feel more vibration in the desk with the bricks. I suspect some additional work on the isolation may further improve the sound.

I went to the hardware store and bought four concrete bricks at a whopping price of $0.47 each. I put two bricks on top of the foam then speaker on the bricks. The concept: if the speaker has more mass the cabinet will move less, allowing a more efficient push/pull of the cone. It’s like giving a sprinter a starting block for a better push off. Sure enough I got my bass back. Not only was the bass full, it sounded tighter and more accurate than any configuration I’ve tried so far. Now one of the consequences is that the foam is carrying a heavier load, which somewhat compromises the isolation; I can feel more vibration in the desk with the bricks. I suspect some additional work on the isolation may further improve the sound.

At some point I’d like to replace these mediocre speakers. But I’ve managed to get some dramatic improvements by simply moving things around and experimenting with low/no cost materials. Which just goes to show that good ideas and the willingness to test them can be far more cost effective than clicking through your PayPal account.

Part of the Right Tools for the Job series, comparing various platforms to work efficiently.

RECORDING ON LOCATION

I’ve dragged a tower, keyboard, mouse and monitor(s) to more location recording sessions than I’d like. Reconstructing a fixed setup on the road may not seem like too much of a chore on occasion. But a desktop machine may cost you significant time (money) if you’re regularly setting it up and tearing it down. All of those connections and options we love on desktop machines are subject to more wear and tear than manufacturers may have intended with all of that setup and take down. I’ve rented racked recording workstations built around desktop machines that were sturdy and powerful, but they were also costly and bulky. A desktop machine can be used for location recording, but it’s rarely elegant.

LOCK UP

It has been years since I’ve needed to synchronize a DAW with a video deck in studio. But on a film set there is no Quicktime video because they’re shooting it! Desktop machines allow the greatest flexibility in choosing synchronization interfaces because most have card slots. This is when a giant, rack mounted rig based on a desktop makes a lot of sense.

TAKE OUT

I am a huge fan of laptop computers for location recording, especially the newer ones that avoid noisy fans. You can find the right combination of connectivity and bandwidth for significant track counts on a laptop. If your interface is well suited for travel a laptop can be the crown jewel of a powerful, time saving recording rig.

I think tablets offer an ideal opportunity for location recording because a touchscreen UI can be as simple and direct as hardware based, dedicated recorders with physical buttons on them.  I’m encouraged to see audio apps support 24bit and a 48kHz sample rate. The overlap with iOS audio and Apple Core Audio devices helps expand interface options. Google’s commitment to audio with Android 4.1 looks promising. Some of the new Windows 8 tablets are threatening to have HDMI, Thunderbolt and USB 3.0 connectors on them. I have hope for the future of pro audio on tablets.

I’m encouraged to see audio apps support 24bit and a 48kHz sample rate. The overlap with iOS audio and Apple Core Audio devices helps expand interface options. Google’s commitment to audio with Android 4.1 looks promising. Some of the new Windows 8 tablets are threatening to have HDMI, Thunderbolt and USB 3.0 connectors on them. I have hope for the future of pro audio on tablets.

Update July 5: Apple will be using a smaller 19-pin connector on the next iPhone.

There’s a USB micro port on my Droid X handheld, but there don’t currently seem to be any USB drivers to support audio recording or playback. That means the best I could record is a high output dynamic mic in mono using the built-in AD converter. The iPhone (and iPad) fair better, but the same limitations discussed for studio recording make handhelds unattractive for high quality location recording. I’m not sure if I hold as much hope for handheld devices as I do tablets due to the smaller form factor. Although it would be great to record in high quality stereo on my phone with a modest interface. That would be incredibly useful for interviews, podcasting, recitals and much more. When portability is the name of the game, handheld is certainly attractive. But I wonder if a bulky audio interface kind of negates that convenience factor.

As with studio recording, tablets and handhelds make great companions for audio folks on the road. I’ve got an RTA app  on my phone that’s great for identifying frequencies when ringing out a reinforcement setup. Is the spectrum accurate? Not terribly, though it’s better when calibrated against pink noise. But when you’re chasing feedback it’s more than enough to quickly identify where the system oscillates. I don’t have much experience with level meter apps, but I suspect they’d be sufficient to find the critical distance in a reverberant space — useful both for live sound and location recording.

on my phone that’s great for identifying frequencies when ringing out a reinforcement setup. Is the spectrum accurate? Not terribly, though it’s better when calibrated against pink noise. But when you’re chasing feedback it’s more than enough to quickly identify where the system oscillates. I don’t have much experience with level meter apps, but I suspect they’d be sufficient to find the critical distance in a reverberant space — useful both for live sound and location recording.

THE FIFTH ELEMENT

Sound Devices field recorder

On the other hand, if you can record into the same workstation you’ll be using for other tasks (editing, mixing) you may gain a time advantage using a computer based platform rather than a dedicated field recorder. I’ve had gigs where we recorded straight into ProTools (locked to the house timecode generator), edited and named recordings in between takes, and delivered audio on a USB thumb drive at the end of the day right before take down. The client loved us! I’ve recorded into my DAW on location, opened the same session back at the studio and went right to work — no transfers, no conversions, no extra steps. I’ve also had my DAW crash on me during location sessions and wished I had a dedicated recorder.

When failure is not an option and timing is critical, I’ve recorded to two independent systems at the same time. Typically the primary recorder is a computer based DAW and the safety is a dedicated recorder. A tablet or handheld might serve well as a recording safety for these situations.

Field recorders are less likely to become obsolete due to software upgrades. The other four platforms will get codependent upgrades to the OS, the application and hardware configurations, forcing you to upgrade the others. A dedicated recording unit will just keep recording. So you may get more life out of a field recorder for a better return on your investment.

CONCLUSIONS

A touchscreen seems perfect for location recording. I have high hopes that tablets will offer increasingly better choices for audio recording. Until then I’ll prefer the power, flexibility and portability of a laptop. I’ll probably continue to drag desktops on the road when I need all of the bells and whistles, and rent field recorders for projects where they make a critical difference, but laptops seem ideal for location recording. I’m less optimistic about handhelds because most hardware needed for professional recording is larger than the phone, minimizing the handheld portability advantage.

Which do you prefer for location recording? Why?

Read more from the Right Tools for the Job series.

Part of the Right Tools for the Job series, comparing different platforms to work efficiently.

RECORDING IN A STUDIO

A studio may be a place of business or simply somewhere that recording gear is setup permanently. Traditionally this is where we tend to see desktop computers used to record. A desktop PC or Mac offers lots of I/O connections  and most likely card slots. These choices allow desktop machines the greatest flexibility in configuration. They tend to have faster processors, more processors, more memory, more bandwidth, and the largest amount of storage both internally and using external drives, servers, etc. For large, complicated projects with high track counts – especially if video is involved – a desktop machine tends to have the required muscle. On the other hand all of those options can leave you confused about how to get setup and solve problems. Desktop machines also tend to need cooling fans, which are noisy. While there are some low cost options for desktop computers, the really powerful ones we like to use for media production tend to cost more. The greatest strength of a desktop machine is the megahertz and terabytes per dollar. And because they are more easily connected to other hardware, they may serve our needs longer than other platforms.

and most likely card slots. These choices allow desktop machines the greatest flexibility in configuration. They tend to have faster processors, more processors, more memory, more bandwidth, and the largest amount of storage both internally and using external drives, servers, etc. For large, complicated projects with high track counts – especially if video is involved – a desktop machine tends to have the required muscle. On the other hand all of those options can leave you confused about how to get setup and solve problems. Desktop machines also tend to need cooling fans, which are noisy. While there are some low cost options for desktop computers, the really powerful ones we like to use for media production tend to cost more. The greatest strength of a desktop machine is the megahertz and terabytes per dollar. And because they are more easily connected to other hardware, they may serve our needs longer than other platforms.

Laptops can be just as powerful as their desktop cousins, but the smaller, lighter form often means fewer connectors. Laptops are often more expensive for the same amount of horsepower as a comparable desktop. The smaller screen can slow you down on those big projects, although screen real estate is less of an issue for recording and most laptops allow you to plug in a second screen fairly easily when needed. Laptops are more difficult to modify. Some have expansion slots but they are usually proprietary — fewer choices for connecting to media production hardware. Some laptops have cooling fans, though many of the high end ones have none or relatively quiet fans, which I applaud. If you record in a studio but also need portability, a laptop is a nice mix of options.

Laptops can be just as powerful as their desktop cousins, but the smaller, lighter form often means fewer connectors. Laptops are often more expensive for the same amount of horsepower as a comparable desktop. The smaller screen can slow you down on those big projects, although screen real estate is less of an issue for recording and most laptops allow you to plug in a second screen fairly easily when needed. Laptops are more difficult to modify. Some have expansion slots but they are usually proprietary — fewer choices for connecting to media production hardware. Some laptops have cooling fans, though many of the high end ones have none or relatively quiet fans, which I applaud. If you record in a studio but also need portability, a laptop is a nice mix of options.

Tablets are known for their intuitive interfaces: you can get up and running quickly with fewer things to go wrong. Most apps are cheaper than what you might buy for your desktop or laptop, meaning you can get started for a lot less. If you want to get something down quickly, or you record voice auditions at home, a tablet could be a cost effective option. I’m not aware of any tablets that have a cooling fan, which helps keep them quiet.  Some of the newer tablets offer as many connectors as a laptop, but the trend has been far fewer. That limits your ability to connect better microphones than what’s built-in. It also makes it difficult to use higher quality mic preamps and analog to digital converters. Proprietary connectors further constrain your choices. Tablets are significantly underpowered, have less storage, and have lower bandwidth than laptops or desktops. One thing especially frustrating about iOS tablets is a lack of centralized file structure. For audio the best file transit seems to be syncing iTunes with a desktop or laptop via USB or iCloud. You could also collaborate via services like SoundCloud. But you can’t simply add an external drive, or drag and drop to another machine. These file management contraints seem to make tablets better suited for listening than recording. And since you may need a laptop or desktop for any heavy lifting, a tablet may not be as cost effective in the long run.

Some of the newer tablets offer as many connectors as a laptop, but the trend has been far fewer. That limits your ability to connect better microphones than what’s built-in. It also makes it difficult to use higher quality mic preamps and analog to digital converters. Proprietary connectors further constrain your choices. Tablets are significantly underpowered, have less storage, and have lower bandwidth than laptops or desktops. One thing especially frustrating about iOS tablets is a lack of centralized file structure. For audio the best file transit seems to be syncing iTunes with a desktop or laptop via USB or iCloud. You could also collaborate via services like SoundCloud. But you can’t simply add an external drive, or drag and drop to another machine. These file management contraints seem to make tablets better suited for listening than recording. And since you may need a laptop or desktop for any heavy lifting, a tablet may not be as cost effective in the long run.

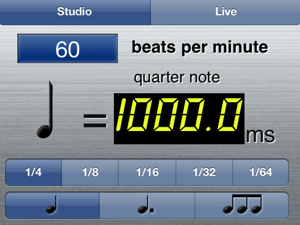

A handheld device is like a miniature version of a tablet with a built-in phone. The smaller form factor further limits options for connectors and expansion. But a handheld fits in your pocket! And because it’s also your phone, chances are you’ll have it with you most of the time. The limited connectivity and considerably smaller screen do not make a handheld nearly as attractive for a centerpiece of your recording studio. As with a tablet, a handheld could be great for recording something quickly, like a song idea or audition.  It’s very important to mention that both tablets and handhelds make great side-kicks in the recording studio. From ordinary tasks — like making a phone call or reading an email — to more studio specific tasks — like Bobby Owsinski’s delay calculator app or documenting your gear settings with a photo — tablets and handhelds can make a critical difference in productivity at a dedicated studio. Top notch voice actors will often bring their own reference for matching (sound-alike). A handheld is great for carrying around reference audio.

It’s very important to mention that both tablets and handhelds make great side-kicks in the recording studio. From ordinary tasks — like making a phone call or reading an email — to more studio specific tasks — like Bobby Owsinski’s delay calculator app or documenting your gear settings with a photo — tablets and handhelds can make a critical difference in productivity at a dedicated studio. Top notch voice actors will often bring their own reference for matching (sound-alike). A handheld is great for carrying around reference audio.

CONCLUSIONS

I love mobile devices for the conveniences they offer, but I’m far more inclined to record with a desktop or laptop given their price to performance ratio, especially when I consider time. Tablets and handhelds do provide a less complicated path for basic tasks. My recording needs so frequently exceed basic that I’m going to need a desktop or laptop either way, so I lean toward them. In studio I like the greater flexibility and horsepower of a desktop.

Which do you prefer for studio recording? Why?

Read more from the Right Tools for the Job series.

This series compares platforms for audio production: Desktop, Laptop, Tablet, and Handheld

What are the advantages and trade offs? How can we make the most of what we already have? What’s the best use of time and money?

Record in Studio

Record on Location

Backup

Edit

Mix

Master

Project Management

Communication

There seems to be plenty of curiosity about video in ProTools, especially the H.264 codec. I’ve previously identified problems using H.264 in ProTools, but let’s take a wider look at how these two interact.

TASTES GREAT / LESS FILLING

If you’ve ever compared video codecs you know H.264 is compact for the quality level it affords. That explains why it’s so popular. The trick is Variable Bit Rate, meaning that each successive frame of picture isn’t fully represented in the data. Most of the time the percentage of stuff that changes frame to frame isn’t high, so the codec just saves the difference. On a static video shot the amount of data needed over time is relatively low. Lots of cuts and motion will require more data. The point is: the amount of memory varies from frame to frame. This can be very efficient in terms of storage, but not in terms of processing overhead. By comparison, Motion JPEG-A is basically the same amount of data for every frame. The files are much larger but it’s easier for your computer to render the image because the data stream is consistent. H.264 requires your computer to work harder, taking more horsepower.

SOUND WITH PICTURE

If that Variable Bit Rate trick sounds familiar it should. AAC (also known as MP4 audio) can vary the bit rate to help keep things smaller. Now take those two codecs and put them together. If the picture is H.264 and the audio is AAC your computer has the increased overhead of decoding two complex streams of data AND it has to keep them in sync! If you have experienced problems with sluggish H.264 video in ProTools, definitely keep away from AAC encoded audio.

WHAT’S A FRAME BETWEEN FRIENDS?

Because the data for a given frame is spread across several other frames, random access of H.264 gets tricky. If you drop somewhere in the ProTools timeline that’s in the middle of an H.264 stream the computer might not have enough data for that frame. So your computer looks back (or maybe forward) to pick up the missing data. That makes it tough for the computer to know exactly which frame to render at any given location. For that reason you may see the wrong frame when you drop the cursor interframe. Let’s say you’re spotting a face slap sound effect. You probably don’t want to be a frame off sync, but that’s exactly what can happen. People who are serious about sync — notably film post and game audio professionals — find H.264 a deal breaker for this reason.

PROTOOLS AND VIDEO

Why is it a video will play fine on it’s own, then die horribly in ProTools? Tough question, but the heart of the issue is how ProTools deals with video.

The ability to play video is built into your OS, not ProTools. So when you play video, ProTools hands off the task. If that task is heavy because you’ve got a big, high resolution video with a variable bit rate, your machine will get busy. When you’re not running ProTools, the video might play fine. But ProTools is a resource hog. If you ask your machine to run ProTools (which tends to tax it) and then ProTools hands off the video playback task (further taxing it), your ProTools may get sluggish. Faster processors, efficient code and tons of memory help video that used to choke machines a few years ago run pretty smoothly today. Moore’s Law means this kind of problem will be less of an issue in the future, but understanding why ProTools bogs down can help you problem solve when you have video trouble.

BEST PRACTICES

By all means, use H.264 to encode and throw those tiny files around to everyone one who needs video. It’s great quality at a low memory price, for quicker up/downloads.

If you need to be frame accurate, convert H.264 to something else before importing into ProTools. I like Motion JPEG-A.

If you use H.264 video and it makes your ProTools rig too slow, first check to see if the audio is AAC. If it is, convert your video or ask for new video with constant bit rate audio.

Slow ProTools and H.264 may simply indicate the limits of your setup. Convert or ask for new video with a smaller frame size, lower quality and/or constrained data rate. In other words, lower the complexity of the stream.

If you’re still having problems with H.264 video after all of that, I say give up. Go ahead and convert to another codec, such as Motion JPEG-A. MPEG Streamclip is free for Mac and Windows, reliable, and can batch convert. (More video conversion options here.)

UPDATE Aug 16, 2012

A video codec based on H.264, called High Efficiency Video Coding (HEVC), is expected from the Motion Pictures Expert Group in 2013.

See also- ProTools + H.264 video = Problem, ProTools: Bounce to Quicktime Movie with Full Options, Conflict: ProTools and Spotlight Indexing, ProTools Sync: The Short Video Problem

Do you have a Pinterest board to collect articles like this one? Cool.

![]()

Interactive storytelling isn’t confined to traditional console games. For example, I was privileged to record dialog for a game that spans an entire theme park! Players become sorcerers, running around the Magic Kingdom in Florida defeating nefarious villains. The game is full of good stuff: animation, collecting magical items, quests, and a wizard named Merlin.

I just hope the kingdom will survive if I need to take a detour through Space Mountain.

Read the Wired Magazine article here.

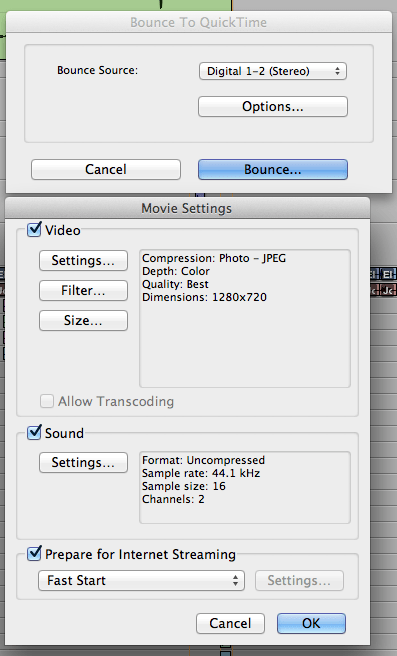

Apparently this has been one of the best kept secrets among post production ProTools users: before you execute a “Bounce to” > “QuickTime Movie…” command, hold down Control-Option-Command.

You will get a different dialog box that includes an “Options…” button.

You will get a different dialog box that includes an “Options…” button.

Click Options and you can manipulate a wide variety of QuickTime specifications for a video file: video codec, frame rate, dimensions; audio format, sample rate, bits, channel configuration; and file streaming optimization.

If you work to picture and need to kick out a different format, this can save you having to work in another application.

As of ProTools 7.2 you’ve been able to do this trick. And apparently it’s been documented on the duc since at least 2006.

I’ve never seen this key combo in any official documentation. I’m not sure why more people haven’t spread the word about it.

Well now you know. And knowing is half the battle.

See also- Conflict: ProTools and Spotlight Indexing, ProTools + H.264 video = Problem, ProTools Sync: The Short Video Problem

Do you have a Pinterest board for an article like this? Go ahead-

![]()

I was privileged to be part of the Soundelux DMG team that opened a new recording studio in West LA. The facility is great for 5.1 mixing, music recording and — of course — voice recording.

Veteran studio makers Bill Johnston and Rich Toenes demonstrated their genius with the features they implemented. Just like the Hollywood studio, the large take counter display increments every time ProTools is thrown into record so that everyone knows the current take number at a glance. There’s a separate talkback system built on the back end of the monitor chain, so you can communicate through headphones, the studio loudspeaker, phone patch or Skype regardless the status of ProTools. This is especially useful when ProTools is closed for file change overs. They installed EdiPrompt, a screen overlay that works with ProTools to automatically display wipes, sound beeps and other talent cueing options for ADR. It’s pretty slick and can save tons of setup and session time [this video details how it works].

The acoustical treatment is variable: they can roll up the plush carpet, take down the panels and move the gobos to go from dead to live. And back again. There are plenty of video displays with multiple inputs in various locations so that clients, the engineer, the production assistant and everyone on the recording stage can see video reference, ProTools, camera feeds and more. All of that infrastructure enables an efficient workflow.

The acoustical treatment is variable: they can roll up the plush carpet, take down the panels and move the gobos to go from dead to live. And back again. There are plenty of video displays with multiple inputs in various locations so that clients, the engineer, the production assistant and everyone on the recording stage can see video reference, ProTools, camera feeds and more. All of that infrastructure enables an efficient workflow.

Leaving such a well made studio after only a few weeks was difficult. When I handed the reigns to recording veteran David Natale I felt like I was asking him to take care of my child. He didn’t seem to mind inheriting the studio.

Leaving such a well made studio after only a few weeks was difficult. When I handed the reigns to recording veteran David Natale I felt like I was asking him to take care of my child. He didn’t seem to mind inheriting the studio.

I’ve known Chip Beaman for many years so it didn’t surprise me that he had been dreaming of a recording stage in West LA, nor that he shepherded the facility to it’s current greatness. If you’re interested to see and hear the place, I’m sure he would LOVE to give you a tour.

As I said before it was my pleasure to work with such talented people during my time at Soundelux DMG, and to help open their new studio in West LA.