My notes from the Oct 20, 2013 presentation at AES 135 Convention in New York:

W28: Practical Techniques for Recording Ambience in Surround

Helmut Wittek

What is ambience? Understanding sound in three layers:

(1) Reverb, Diffuse Noise

Diffuse, location-independent, not localized, room information.

Must be de-correlated, balanced energy distribution.

(2) Early Reflections, Discrete Sounds (spread)

Discrete, location-independent, localized, but the location is arbitrary, info on position of the source in the room.

Must be correlated, balanced directional distribution.

(3) Discrete Sounds

Discrete, location-dependent, localized, source information.

Must be correlated.

Larger distance between the two mikes

More directional mic patterns

Greater angle between mikes

DFC: Diffuse Field Correlation

Arrays can be built using the Image Assistant Java applet and/or the Michael Williams curves.

After the session I spoke with Helmut about using boundary layer techniques to record ambience. We agreed: this could work very well to achieve de-correlation, but the necessary size of the movable boundaries would render such an approach far less practical than any of the arrays demonstrated.

Helmut’s full presentation plus all of the surround sound demonstration files are available here.

Michael Williams

5 channel umbrella, 12 channel umbrella, 16 channel array including height information

Unified Perspective:

All sound is recorded at the same time; there are no layers. The layer concept provides additional control for later in the process whereas array placement is absolutely critical for the Williams arrays. But layers are to sound what hamburgers are to food, whereas the Williams arrays are “like fine French cuisine.”

The 5, 12, and 16 mic arrays are scalable: turn on as many microphones as there are speaker channels.

2nd volume of his book is now available. I bought it.

A collection of papers about recording by Michael Williams, plus his Multichannel Microphone Array Design pages here.

For more convention presentations, photos, audio gear, etc. see: 135th AES NY Roundup

My notes from the Oct 18, 2013 presentation at AES 135 Convention in New York:

G4: Loudness in Interactive Sound Roundup

by Garry Taylor at Sony

1 LU = 1 dB (sort of…)

EBU Tech 3342 is the TC authored paper about loudness range. The top and bottom 10% are discarded in the TC loudness range measurement. EBU recommendation for home use is a loudness range of 20 LU.

Why standards?

Users deserve a consistent loudness experience.

We want to promote good engineering practices.

Protect the format (and equipment) used to deliver content.

Codecs don’t deal with clipping very well.

Headroom is very important when downmixing from multi-channel to stereo.

Sony’s standards for loudness:

PS3 / PS4: -24 LUFS +/-2

PSVita (mobile): -18 LUFS +/-2

True Peak should not exceed -1 dBTP

Loudness Range (LRA) should not exceed 20 LU

There is loudness code that runs on PS4 development tools. Developers must measure their games and submit the reports, but are not automatically held back if missed.

DSP limiters onboard are not currently True Peak, so they set standard limiters at -1.5dB, which MAY exceed -1 dBTP.

Audio should be measured as a whole, not dialog or other isolated content specifically.

Splash screens are measured separately from gameplay.

Titles should be measured for a minimum of 30 minutes with no maximum, targeting a representative cross-section of all game play.

Loudness testing happens at the very end of development. Make a great sounding game first!

Loudness in interactive entertainment is an inexact science – because content is presented based on player activity.

These best practices are informing a set of parameters for content creators, especially for dialog localization.

IESD is working on recommendations for mobile games.

For more convention presentations, photos, audio gear, etc. see: 135th AES NY Roundup

Yesterday I took notes at an AES Panel titled Producing Across Generations: New Generations, New Solutions – Making Records for Next to Nothing in the 21st Century. This isn’t a transcript, just a collection of things that I found inspiring. Enjoy.

Moderated by Nick Sansano

Seated Left to Right, older to younger: Frank Filipetti / Bob Power / Craig Street / Hank Shocklee / Carter Matshullut / Jesse Lauter / Kaleb Rollins (K-Quick)

Carter Matshullut: Small labels can serve as taste-makers.

Bob Power: Limited resources often help make a record interesting.

Frank Filipetti: “You have to be scalable to survive.” “You have to temper budget with what got you into this business: the love of music.”

Hank Shocklee: I spent $12k on Fight the Power. “I never had any budget.” We would work 3am – 9am to get cheap rates. Chung King was used to record My Uzi Weighs a Ton. Your records are basically a flyer, a promo item to sell shows. “Whatever you don’t have is what fuels your creativity.” I sampled because I couldn’t afford a drummer. Technology is vital.

Frank Filipetti: Limitations force decisions… Sgt. Peppers sounds like it does because it was recorded on a 4 track. People are not being forced to make decisions so a mixer now must do that. The decisions caused by limitations informed the record. Making decisions early on – having that limitation – forces you to think and plan more about the sound of the record early.

Bob Power: Freshness and creative energy are important. You need to maintain the musician’s enthusiasm. Tedious work during tracking can kill the energy.

Craig Street: “Analog is really nothing but an attitude.” Give yourself limitations. Don’t do so much because you can. Do what the song needs. You’re just trying to capture a great performance.

Frank Filipetti: “Be really gear agnostic.” “There is no piece of gear that you have to have to make a record.” “It’s not the gear.” There isn’t anything you could buy for even $100 that couldn’t be used to make a great record.

Bob Power: You need to participate in artist development.

Frank Filipetti: You’ve got to have a video running during the recording session now too.

Hank Shocklee: “I never wanted to be a record producer. I only do what I like. And what I like, I see it through all the way to the end.”

Bob Power: Developing the broadest skill set that you can helps you survive and ultimately become a better practitioner.

Hank Shocklee: The mastering engineer is the key specialist now.

Kaleb Rollins: How can I do this on my own terms? I setup a recording studio in my dorm room and charged people. Early on we had to pay the bills so we took any session that came along just to pay those bills. When you can find good artists who actually have good money, that’s amazing.

Carter Matshullut: Branding is a big deal for younger producers, to come in and make things “cool.” There is the hustling side of it – studio in the dorm. Be able to answer the question: Why should I hire you?

Bob Power: People pay you for heart and sole. They want you to help them make their dreams come alive. Give more than the artist will give themselves.

Nick Sansano: Younger practitioners seem to have an innate sense of branding.

Carter Matshullut: Royalties are a distant hope in many genres. Sometimes producers take jobs because the project is cool and will get some buzz.

Hank Shocklee: “I’m hearing 808s in Country Records.” I want to do things like Baskin And Robbins where they put interesting things together.

Jesse Lauter: You gotta know if you are right for the job. “I knew I wasn’t the right person for the job.”

Frank Filipetti: I really admire the young people, how they go after everything. I am not a multi-tasker. “But I can concentrate like a motherfucker.” When your eyes are open, too much of your brain is used on visuals. I like to mix with my eyes close. “When someone pours their heart and sole into something there is really something to it.”

For more convention presentations, photos, audio gear, etc. see: 135th AES NY Roundup

There are many ways to prevent plosives in voice recordings. My favorites are the simple ones. When I record voice my first two lines of defense are:

There are many ways to prevent plosives in voice recordings. My favorites are the simple ones. When I record voice my first two lines of defense are:

(1) Mic placement, and

(2) A low rolloff before compression.

A few weeks ago my friend and colleague Ethan Friedericks was recording a child actor. She was very professional and did a great job, but Ethan and I noticed some “p” popping despite good mic placement, a low rolloff, and a nylon covered pop filter. I’d heard of people using a second pop stopper, but never actually witnessed it. On a break we decided to try it, and it worked like a charm.

WHY DOES IT POP?

I find that choosing a technique has a lot to do with root causes; understanding why plosives happen can lead to a solution.

When we form P, T, and B letter sounds a gust of air leaves the mouth. Just put your hand in front of your mouth and feel the blast you create. Microphones convert moving air patterns into electrical patterns. The burst of air from P, T, and B sounds has significantly more force on the microphone element than other air vibrations made by a mouth. The sound of the air hitting the capsule is unnatural and distracting. With rare exception (beat boxing) plosives are undesirable.

The sound of the air alone usually isn’t too distracting or difficult to avoid. But another factor creates the real challenge: Proximity Effect. Directional microphone patterns — such as cardioid — overemphasize bass frequencies at close range. A gust of air up close can sound like a bomb going off, especially with a monitoring environment that allows listeners to hear the bottom octaves.

Most techniques for minimizing plosives either address the gust of air, or the exaggerated bass response of proximity effect. But there is one approach that deals with both: mic distance.

SUMMARY OF TECHNIQUES

- Move the mic farther away from the mouth where the air blast is less powerful AND there is less proximity effect.

- Place the mic out of the direct line of fire for air leaving the mouth, usually above or to the side.

- Low rolloff before compression.

- Typical pop stopper: nylon stretched over a ring. Some use two fabric layers with a gap between.

- Variations of the nylon ring that use wire mesh, perforated metal plates, and other wind blocking materials.

- Foam sock that slips over the mic, or is built into some mikes such as the Shure SM58.

- Less directional mic pattern. Pops are almost impossible with omni mikes and can be used very closely.

Each of these approaches has audible side effects, so it’s nice to have options. As you may have noticed, I will often use several techniques at the same time. Happy voice recording!

UPDATE Oct 18:

Gary Terzza of VO Master Class provides this useful technique for placing a pop stopper for maximum effectiveness:

“Place your hand (palm facing towards you) between the pop shield and the mic and blow gently. Now move the popper slowly towards you while still blowing. Stop at the point you can no longer feel the breath. This is the optimum point at which the air is diffused, stopping those intrusive Ps and Bs.”

See also: Things to listen for when choosing a vocal mic by Ben Lindell

I like this video for two reasons.

(1) The insight for actors is elegant and inspiring.

(2) It begs the question for the rest of us: what is the essence of your calling? For example, most people I work with don’t want to talk about audio gear, they just want confidence that I know how to use it to capture great performances.

Knowing the intrinsic value of your craft not only helps you do it well, it allows you to let go of insignificant things. Such an ability to shed distractions and focus on what’s important sounds like a good start on finding a little career fulfillment.

See Also:

See Also:

The Importance of Being Wrong

Hammer Everything

Pinterest: Actors

Recordinghacks and Audio Technica put the new AT5040 microphone in my hands so we could hear how it sounded on some voices. For a fair comparison we recorded two microphones at the same time with a pristine signal path and no processing. But I wondered how things would change if I processed the voice recordings. Would it reveal greater contrast? Would new aspects be discovered?

So I started with a template and adjusted things until it sounded good. Have a listen to these recordings of voice actor Stephanie Sheh after processing. Each time we hear the AT5040 followed by the Neumann u87Ai.

The difference in presence was most obvious to me in the projected read. At first the presence was the ear catching difference for the intimate read too, but then I noticed the low end change. While neither mic sounded especially sibilant to me, the 3k to 9k Hz range sounded more natural on the AT5040 across all reads. I think either one of these microphones might be a good choice on Stephanie’s voice depending on the project.

This comparison also available via YouTube.

Hear the unprocessed recordings of Stephanie and others.

Listen to other microphone comparisons.

More about voice processing.

We were overjoyed with the way Kari Wahlgren brought the words to life:

Ashley Kaye (producer), Kari Wahlgren (voice), Vickie Saxon (wordsmith), and yours truly.

Kari sounds great on any microphone, so recording her with a Neumann m149 was icing on the cake. Kudos to engineer Nic Baxter (not pictured) at Igloo for another great recording session.

On July 30th the Los Angeles chapter of the Audio Engineering Society hosted a presentation by Julian David featuring guitar player Douglas Showalter titled “Ribbon Microphones: Life Beyond the Figure-of-8 Pattern.” I enjoyed hearing the difference between some ribbons that were not the native bi-directional pattern: an RCA 77 DX, RCA MI-6203/6204 Varacoustic, RCA BK-5B, and the AEA KU4. He threw in a classic RCA 44 (which is bi-directional) just for good measure.

We heard the 77 DX and Varacoustic in different pattern settings. Douglas played his guitar closer and farther from the microphones so we could hear the changes in color. We even listened at 180 degrees and 90 degrees off axis. I had no experience with the Varacoustic nor the BK-5B, so it was a treat to hear them.

As both a recording engineer and mic designer, Julian’s presentation included some operational theory and a look at the inner workings of some ribbon microphones. He passed around a labyrinth from inside a rare RCA KU-3a (10,001) microphone. You can see the cavity is filled curly cow hair! At the time these classic mikes were made, it was determined that cow hair worked well as a frictional absorber. More efficient, stable, and consistent sounding materials are available now.

This was also my first time to see a Beyerdynamic M160 element, the famous “piston” design where the ribbon is crimped width-wise rather than the traditional length-wise. Plosive protecting mesh has been pulled back to see the detail of the ribbon element.

Wes Dooley was present and shared his ribbon mic wisdom too. He and Julian both confirmed a suspicion I had about all directional microphones: There is NO proximity effect at 90 degrees off axis, regardless the type of microphone element used. Good stuff.

Kudos to everyone for a thought provoking evening!

See also:

How A Unidirectional Ribbon Mic Works

Unidirectional Ribbon Mic Shootout

The $60,000 Ribbon Mic Shootout

The best approach to sibilance would be changes in mic placement and selection during recording. But if you were not the recordist, you may have inherited someone else’s poor choices and get a voice recording where “S” sounds are painfully harsh. If this happens a few times during a recording, applying EQ to only those instances may be a good solution. But if you have consistent sibilance throughout, manually highlighting and EQing each “S” can be time consuming.

Sometimes we magnify the problem: harshness can be exaggerated by extreme compression, in which case backing off may be helpful. Other times a surgical EQ cut on the entire recording may alleviate sibilance without otherwise damaging the sound of the voice. Maybe an adjustment of compression plus an EQ cut does the trick. Never overlook simple solutions like these. But when a raw voice recording sounds obviously sibilant even before you strap a compressor across the channel, you may need a de-esser.

For a voice recording that is sibilant all the way through, there is typically a dominant frequency where the sibilance peaks. Sometimes an RTA is a quick way to visually find this frequency. You can also sweep the 3-12k Hz region with a narrow Q parametric and listen for the offending frequency. Finding a dominant frequency allows you to use it for triggering a de-esser, and may also be used to focus the processing on the appropriate band if the de-esser is capable.

THE FIRST SHALL BE LAST

De-essing is one of those processes I like to employ early in the chain. The way I figure it, the sibilance volume is probably more consistent before other processing rather than after. For the same reason, whenever I use a gate plug-in I also tend to insert it immediately following the initial cuts. But I know people who’ve suggested just the opposite, so decide for yourself where in the signal path de-essing, gating, or other miscellaneous functions seem effective to you.

TUNED GAIN REDUCTION

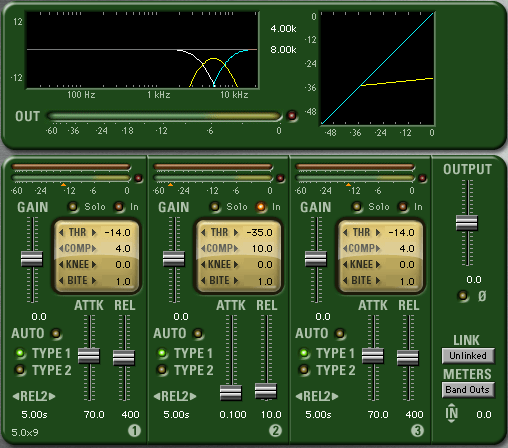

One way to learn how something works is by taking it apart and/or building one. At it’s core a de-esser is a compressor with frequency specific controls. So let’s use an EQ plug-in and a separate compression plug-in to make a basic de-esser. We’ll use different plug-ins on each track, so be sure delay compensation is active.

Duplicate the sibilant voice track. Place a compressor with side-chain capability on the first track. Use a narrow bandpass on the second track so that the sibilance is promenant, then buss the output to the side-chain input of the compressor on the first track. Activate the side-chain and set the compressor threshold so that strong sibilance content causes the compressor to clamp down on the voice signal. If the threshold is too high, the sibilance won’t be reduced. If the threshold is too low, the “S” sounds will resemble a lisp; that’s how you know you’ve gone too far. Use quick attack and release times to help keep the compression out of the non-sibilant parts of the signal. A high ratio usually works well.

Congratulations! You just built your own de-esser. Notice a few things:

(1) Gain reduction should be driven by a fairly narrow bandwidth that is “tuned” to the sibilance.

(2) The threshold must be significant enough to reduce some sibilance without sounding lisp-like.

(3) The EQ is not applied to the signal, only the side-chain. So the full bandwidth signal gets reduced when the compressor triggers. Sometimes the quick attack and release settings are not enough to prevent other sounds from being compressed too.

HIGH FREQ GAIN REDUCTION

As we have seen, sometimes broadband compression will affect non-sibilance. Let’s consider a more focused version of the de-esser in an attempt to improve performance. This time we separate the high frequencies and subject them only to compression.

Start again with only one vocal track. Make two duplicates; three tracks total. On the first track use a high pass (low rolloff) filter. Set the frequency just below where the sibilance dominates. For example, if the harsh “S” sounds are centered at 6k Hz, then set the high pass on your first track to 4k or 5k Hz. Add a side-chain compressor after the EQ.

On the second track use a low pass (high rolloff) set to the same frequency as track one. This will be the part of the voice that the de-esser does not touch.

On the third track setup your band pass filter, centered on the sibilance. Feed the output of the third track to the side-chain input of the compressor on the first track.

This de-esser is a little more complicated, but narrows the focus of the gain reduction. It provides the opportunity to sound more natural. The threshold setting is still important: too little compression and the sibilance will remain, too much and the lisp-like sound results. Many of the de-essers that you can purchase function like this.

BAND PASS GAIN REDUCTION

So far both of our DIY de-essers use a bandpass filter to drive the side-chain of a compressor. What if we wanted to compress only that band of sibilance and leave everything below and above it alone? Here’s how to built it:

Start again with only one vocal track. Make two duplicates. Slap a low pass filter (high rolloff) on the first track. This will be all of the voice below the sibilance that we leave alone.

On the second track use a high pass filter set to the same frequency as the first track. Add a low pass filter above it. The low pass and high pass filters combine to make a band pass filter. These two frequencies should be set for the lower and upper limits of the sibilance range that you want to diminish. Now add a compressor. Since the input of the compressor is the sibilance, no need to use a side-chain input. Just compress the sibilance and leave the rest alone.

The third track will need a high pass filter set for the same frequency as the low pass filter on the second track. This will be all of the voice above sibilance that we leave alone.

I think it’s worth building all three tracks to really understand how the parts work together to de-ess. Some of the better de-essing processors available for purchase have a similar band pass option.

But now that we’ve built the whole thing, let’s take a short cut with a multi-band compressor. If you simply insert the multi-band compressor on a single track of voice, then define one band’s lower and upper limits like we did the second track above – boom! You’ve essentially created the same de-essing process with a lot less fuss. Leave the other bands inactive and you will only process the sibilance. Most multi-band compressors have presets for de-essing and they could be a good starting point when you’re trying to manage sibilance.

LISTEN

Many dedicated de-essers have a “listen” function that allows you to tune around and listen to the strength of the signal used to activate the gain reduction. This saves time because once you find the harshness, you’ve simultaneously set your de-esser to use it. It can also be more intuitive than looking at an RTA or sweeping and listening to a parametric EQ.

DE-ESSER KUNG FU

The trickiest de-esser I know was originally built into the Empirical Labs Lil Freq, then got it’s own half rack called the DerrEsser. What makes this processor unique is that it not only reacts to the strength of the tuned sibilance band, but it compares it to the audio out of band. All other de-essers can misfire if a signal is simply very loud. If the sibilance band happens to be strong because everything is strong, the threshold may be crossed and the de-esser activates even though there may be no sibilance. The Empirical Labs processor compares the sibilance band to the rest of the signal. If everything is loud, then the relationship of the sibilance band to the rest of the signal is relatively flat. But if a harsh “S” sound comes through, the strength of the sibilance band will be much louder than the rest of the signal. This helps the processor activate only in the presence of sibilance and avoid misfiring any other time. It’s very cleaver and one of the best sounding de-essers I have ever used. The only problem is: both the Lil Freq and DerrEsser and completely analog, so there is no plugin option.

I’ve drawn some pretty elaborate schemes on the backs of envelopes to make my own version of this processor for use In The Box, but had a difficult time using it. The interplay of component parts is complicated. So kudos to Empirical Labs for making a great sounding product, with a simple-to-use interface that’s difficult recreate. I’m holding my breath that they make a digital version (I’ve suggested it to them at trade shows).

A SHOCKINGLY SIMPLE DIY DE-ESSER

De-esser function is complex, so I decided to save this technique for the end of the article. Because this version is so incredibly simple, it doesn’t break down the process as well. But it’s super fun and anyone with the most basic EQ and compressor can build it. Plus, it can also provide some insights into voice processing chains more generally. Ready? It’s goes like this:

Parametric EQ boost of sibilant frequency range > compressor > reciprocal cut of the boost

There is only one channel and you don’t need a side-chain! Yes, this is a functional de-esser and it works. Try it for yourself. Astute observers will point out weaknesses of this design:

(1) Ridiculously strong EQ levels must be used to avoid misfires.

(2) Even the highest quality digital EQ used this severely will probably impart undesirable sonic artifacts.

But now consider a variation on this theme. Take the case of a recording that is sibilant and kind of bright overall. Normally you might decide that a modest EQ cut at the sibilant frequency sounds better than a constantly misfiring de-esser. But if you are also using a compressor on that bright recording, you might want to cut the sibilance after compression because that compressor might dynamically help you manage the harshness (especially if your attack and release times are quick). Or you might intentionally choose a bright microphone to recording someone sibilant, let a compressor react to the harshness, then balance out the brightness with some EQ cuts after compression.

You’re probably better off planning for a good recording than a bright, sibilant one, but you never know when an offbeat idea like this might come in handy. The interplay of EQ and dynamics processors is at the heart of every de-esser, so thinking about them in a larger context of component parts in a signal chain can help us use them more effectively.

All of my screen shots are from ProTools, because that’s what I use. To see examples with other software, and de-esser perspectives from other audio craftsmen, check out:

Jon Tidey – Audio Geek Zine – examples in Reaper

Jon demonstrates four different approaches including screen shots and audio examples.

Joe Gilder – Home Studio Corner – examples in Studio One

Watch and listen to this video where Joe configures a multi-band compressor as a de-esser, and adjusts settings based on what he’s hearing.

Also in this Voice Processing series:

Frequency Cuts

Compression Effects

Compression Technique

Frequency Boosts

Extreme EQ!

Limiting